The idea to build a school-centered housing model first came from a Baltimore elementary school principal. He questioned the sanity of putting his housing unstable students in taxi cabs each afternoon for long drives back to shelters and friends’ couches when there were vacant houses right across the street. Baltimore, known for its plethora of vacant row homes, could instead turn these houses into homes for school-aged families. The units could be managed under the Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD) and the placement of the students would be under the control of the neighborhood school, solving both a neighborhood development and housing instability issue simultaneously. The idea took hold, and thus began a partnership among DHCD, Baltimore City Schools, UPD Consulting (where I served as director), and Fannie Mae (who provided the support to build the model through their Innovation Challenge fund).

Building a Theory of Action

But to move from idea to plan required a focused theory of action (an if/then hypothesis), to serve as a North Star for the work. As Chip and Dan Heath might say in their book, Switch, this was a “point to the destination” moment where we must help every stakeholder gain clarity on exactly where we needed to go with this new model. And we would do it by answering: what are the specific outcomes we seek to accomplish by implementing this pilot, and what are the key strategies we will implement to get to these outcomes?

We had done our research on the importance of housing stability for young children prior to even applying to Fannie Mae for the Challenge Initiative funding, often citing the National Child Traumatic Stress Network’s research findings that homeless children have twice the rate of learning disabilities and three times the rate of emotional and behavioral problems of stably housed children and were twice as likely to repeat a grade. (You can read about other adverse outcomes in this Urban Institute article.) We knew that housing was critical to improved life and educational outcomes for these children. But it wasn’t enough to say “improved education and life outcomes.” We needed to get specific.

Vetting the Feasibility of Academic Outcomes

We formed a steering committee composed of an enthusiastic and accomplished group of Baltimore-based housing, education, homelessness, and community experts. And they, in turn, helped us connect with local stakeholders and national experts across the country. “This work isn’t going to mean much if kids aren’t improving academically,” was the oft repeated phrase by those interviewees. Many of them pointed to increased standardized state test scores as our ultimate proof point. Sometimes that sentiment was sincere, based in a real belief that housing students would show test improvement. Sometimes the advice was more cynical, a caution that we were not going to get buy-in from leaders if you don’t name scores as the primary target for the work.

But we knew from our research and a few candid responses in these interviews that there was little to no evidence that housing stability would substantially improve test scores for these students, at least in a short time period. And we knew there were plenty of reasons why a student’s life and academic outcomes may improve but their test scores stay the same, including bias within the test content and format, student test-taking ability, the alignment of the classroom curriculum to the test, and the skill-level and experience of the teacher to effectively teach that curriculum to multiple types of learners.

“If not test scores, then, how about grades?” was the next round of discussion. Questions abounded on how those grades are standardized and can be trusted across teachers and schools. But deeper than the reliability of the data was a question of what was ultimately important. If we piloted the model and students did not show academic improvement, would we throw in the towel on the model and say we think those students would be better off without stable housing options?

The answer was “no,” of course. So, then something else, perhaps more fundamental to child well-being, should be driving this work.

Focusing on a More Critical Set of Outcomes

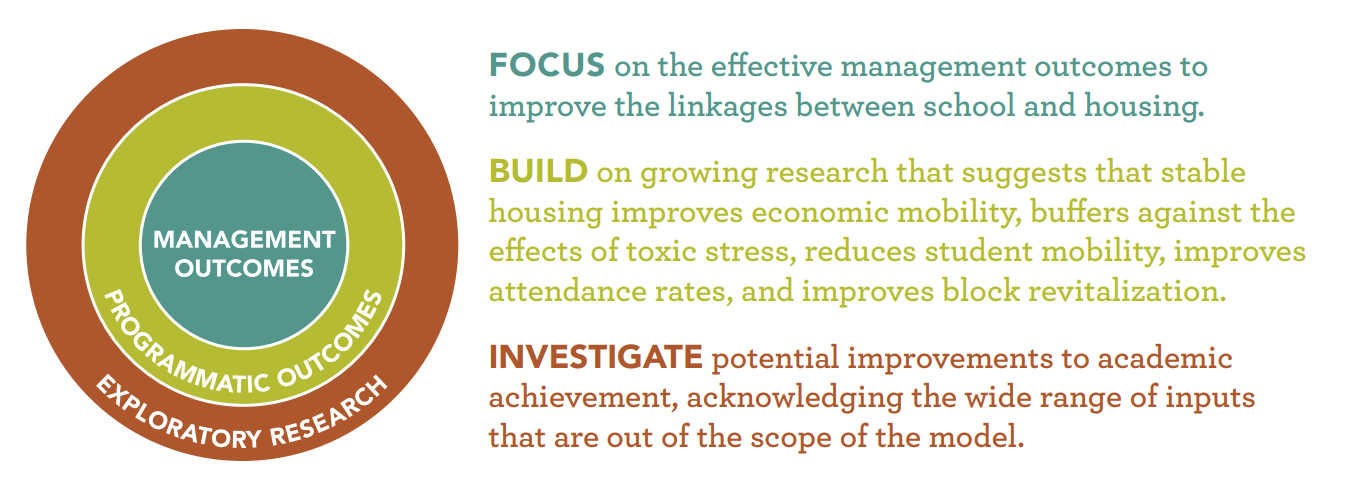

After a healthy amount of research and debate, the steering committee agreed to a set of tiered outcomes, which we likened to a bullseye. It had, perhaps, a surprising center. Once we really broke down the issues and what we were trying to do, we realized that at the very heart of this work was a basic task – to prove we could even build a model with shared ownership between two government agencies, the Department of Housing and Community Development and the school district. It may not be headline making, but it was the foremost objective we needed to meet.

Afterall, we could still house families with young children without that linkage. Baltimore does so now through a variety of housing programs. The concept only works if it makes that service more efficient and effective.

The middle ring is where we built in the programmatic outcomes, ultimately setting on the ideas above in yellow. I will note that student behavior was suggested and rejected because we believed those data ultimately reflect the mindsets and actions of the adults issuing detentions/suspensions and is not a pure indication of each child’s behavior. The inclusion of the attendance rate metric was also hotly debated. As one keen steering committee member pointed out, these young housing-unstable students might already have good attendance. Parents were largely in control of getting elementary students to school and this was, at its most basic level, free childcare. In the end, we kept it in, along with a focus on family income stability (which typically improves with stable housing), student mobility between schools (which can have positive affects not only for affected families but the entire school population), neighborhood revitalization at the block level, and most importantly (at least in my opinion) reduced student trauma as measured by their Adverse Childhood Experiences score.

Finally, the outer red ring was where we placed the academic achievement, acknowledging that these outcomes were important to measure and learn more about, but would not serve as a central focal point for this work. By creating this outer ring we could address the questions so many stakeholders had on their minds but not risk centering the entire work on those outcomes. In essence, the rings told the truth about what we expected to see. And when we started circulating the outcomes, the sky not fall in on us. We got a few raised eyebrows and some concerned questions, but all of this gave us the opportunity to tell our outcome story. And ultimately we found that our stakeholders generally agreed with us.

The bullseye begat the theory of action below and its associated list of outcome measurements beneath it.

A Clear Path toward a Feasible Housing Model

This model is, of course, so much more than its theory of action, but it is the thoughtful decisions of the steering committee on precisely this early and fundamental piece of the program that set the stage for so many other good decisions. As an example, we were also advised repeatedly to create rules for parent participants, including special classes on things like personal finance and requirements to attend Parent Teacher Association meetings. But our thoughtful and thorough vetting of the theory of action set the steering committee up to easily pass on these stipulations, as they were not central to the outcomes we seek (and also paternalistic).

The theory of action didn’t just prevent unnecessary additions to the model, it also inspired us to think deeper on the essential aspects of the work. The center of the bullseye focused our efforts on a well-defined governance structure among the multiple agencies needed to bring life and sustainability to the model. Our commitment to economic mobility and reduced trauma (middle ring) pointed the way to a flexible methodology for more personalized and robust wrap-around supports. It also informed our family selection criteria, prioritizing families with younger children to intervene earlier in the lives of those children and provide the option of longer-term support.

You can read more about the design aspects of the school-centered housing response (SCHORE) model in the white paper linked below.

I’m always interested in talking about ways we can get more children into stable housing through SCHORE and other innovative models. You can reach me at ann@shiftforwardllc.com.